Osteogenesis Imperfecta Types

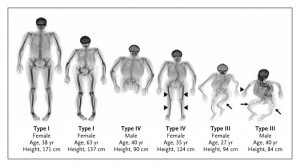

Type I:

- OI Type I is the mildest and most common form of the disorder. It accounts for 50

percent of the total OI population.

• Type I manifests with mild bone fragility, relatively few fractures, and minimal limb

deformities. The child might not fracture until he or she is ambulatory.

• Shoulders and elbow dislocations may occur more frequently in children with OI than in

healthy children.

• Some children have few obvious signs of OI or fractures. Others experience multiple

fractures of the long bones, compression fractures of the vertebrae, and chronic pain.

• The intervals between fractures may vary considerably.

• After growth is completed, the incidence of fractures decreases considerably.

• Blue sclerae are often present.

Guide to Osteogenesis Imperfecta for Pediatricians and Family Practice Physicians 6

• Typically, a child’s stature may be average or slightly shorter than average as compared

with unaffected family members, but is still within the normal range for the age.

• There is a high incidence of hearing loss. Onset occurs primarily in young adulthood, but

it may occur in early childhood.

• Dentinogenesis imperfecta is often absent.

• OI Type I is dominantly inherited. It can be inherited from an affected parent, or, in

previously unaffected families, it results from a spontaneous mutation. Spontaneous

mutations are common.

• Biochemical tests on cultured skin fibroblasts show a lower-than-normal amount of type I

collagen. Collagen structure is normal.

• People with OI Type I experience the psychological burden of appearing normal and

healthy to the casual observer despite needing to accommodate their bone fragility.

• The absence of obvious symptoms in some children may contribute to problems at school

or with peers.

• Significant care issues that arise with OI Type I include gross motor developmental

delays, joint and ligament weakness and instability, muscle weakness, the need to prevent

fracture cycles, and the necessity of spine protection. (See “Behavioral and Lifestyle

Modifications,” page 13.) Children with OI and their parents will need emotional support

at each new developmental stage. Family members should carry documentation of the OI

diagnosis to avoid accusations of child abuse at emergency rooms.

• The treatment plan should maximize mobility and function, increase peak bone mass, and

develop muscle strength. Physical therapy, early intervention programs, and as much

exercise and physical activity as possible will improve outcomes.

Type II:

- OI Type II is the most severe form.

• At birth, infants with OI Type II have very short limbs, small chests, and soft skulls.

Their legs are often in a frog-leg position.

• The radiologic features are characteristic and include absent or limited calvarial

mineralization; flat vertebral bodies; very short, telescoped, broad femurs; beaded and

often broad short ribs; and evidence of malformation of the long bones.

• Intrauterine fractures will be evident in the skull, long bones, or vertebrae.

• The sclerae are usually very dark blue or gray.

• The lungs are underdeveloped.

• Infants with OI Type II have low birth weights.

• Respiratory and swallowing problems are common.

• Macrocephaly may be present. Microcephaly is rarely present.

• Infants with OI Type II usually die within weeks of delivery. A few may survive longer;

they usually die of respiratory and cardiac complications.

• OI Type II results from a new dominant mutation in a type 1 collagen gene or parental

mosaicism. Similar extremely severe types of OI, Types VII and VIII, can be caused by

recessive mutations to other genes. (See “Type VII” and “Type VIII,” pages 9 and 10.)

• Genetic counseling is recommended for parents of a child with OI Type II before any

future pregnancies.

• Significant care issues that arise with OI Type II include obtaining an accurate diagnosis,

Guide to Osteogenesis Imperfecta for Pediatricians and Family Practice Physicians 7

getting genetic counseling, the family’s need for emotional support, and management of

respiratory and cardiac impairments. Infants with OI Type II who can breathe without a

respirator and those with severe OI Type III may be candidates for off-label treatment

with bisphosphonates. At this time, pamidronate (Aredia*) is the only bisphosphonate

that has been studied in infants who have OI. Treatment research is ongoing. (See “Drug

Therapies – Bisphosphonates,” page 15.)

*Brand names included in this publication are provided as examples only, and their inclusion does not mean

that these products are endorsed by the National Institutes of Health or any other Government agency. Also, if a

particular brand name is not mentioned, this does not mean or imply that the product is unsatisfactory.

Type III:

- OI Type III is the most severe type among children who survive the neonatal period. The

degree of bone fragility and the fracture rate vary widely.

• This type is characterized by structurally defective type I collagen. This poor-quality type

I collagen is present in reduced amounts in the bone matrix.

• At birth, infants generally have mildly shortened and bowed limbs, small chests, and a

soft calvarium.

• Respiratory and swallowing problems are common in newborns.

• There may be multiple long-bone fractures at birth, including many rib fractures.

• Frequent fractures of the long bones, the tension of muscle on soft bone, and the

disruption of the growth plates lead to bowing and progressive malformation. Children

have a markedly short stature, and adults are usually shorter than 3 feet, 6 inches, or

102 centimeters.

• Spine curvatures, compression fractures of the vertebrae, scoliosis, and chest deformities

occur frequently.

• The altered structure of the growth plates gives a popcorn-like appearance to the

metaphyses and epiphyses.

• The head is often large relative to body size.

• A triangular facial shape, due to overdevelopment of the head and underdevelopment of

the face bones, is characteristic.

• The sclerae may be white or tinted blue, purple, or gray.

• Dentinogenesis imperfecta is common but not universal.

• The majority of OI Type III cases result from dominant mutations in type I collagen

genes. Often these mutations are spontaneous. Similar extremely severe types of OI,

Types VII and VIII, are caused by recessive mutations to other genes. (See “Type VII”

and “Type VIII,” pages 9 and 10.)

• Genetic counseling is recommended for asymptomatic parents of a child with OI Type III

before any future pregnancies.

• Significant care issues that arise with OI Type III include the need to prevent fracture

cycles; the appropriate timing of rodding surgery; scoliosis monitoring; respiratory

function monitoring; the need to develop strategies to cope with short stature and fatigue;

the family’s need for emotional support, especially during the patient’s infancy; and the

off-label use of bisphosphonates. (See “Drug Therapies – Bisphosphonates,” page 15.)

• It is also important to address difficulties with social integration, participation in leisure

activities, and maintaining stamina.

• The treatment plan should maximize mobility and function, increase peak bone mass and

Guide to Osteogenesis Imperfecta for Pediatricians and Family Practice Physicians 8

muscle strength, and employ as much exercise and physical activity as possible.

Type IV:

- People with OI Type IV are moderately affected. Type IV can range in severity from

relatively few fractures, as in OI Type I, to a more severe form resembling OI Type III.

• The diagnosis can be made at birth but often occurs later.

• The child might not fracture until he or she is ambulatory.

• People with OI Type IV have moderate-to-severe growth retardation, which is one factor

that distinguishes them clinically from people with Type I.

• Bowing of the long bones is common, but to a lesser extent than in Type III.

• The sclerae are often light blue in infancy, but the color intensity varies. The sclerae may

lighten to white later in childhood or early adulthood.

• The child’s height may be less than average for his or her age.

• Short humeri and femora are common.

• Long bone fractures, vertebral compression, scoliosis, and ligament laxity may also

be present.

• Dentinogenesis imperfecta may be present or absent.

• OI Type IV has an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. Many cases are the result

of a new mutation.

• This type is characterized by structurally defective type I collagen. This poor-quality type

I collagen is present in reduced amounts in the bone matrix.

• Significant care issues that arise with OI Type IV include the need to prevent fracture

cycles; the appropriate timing of rodding surgery; scoliosis monitoring; the need to

develop strategies for coping with short stature and fatigue; the family’s need for

emotional support, especially during the patient’s infancy; and the off-label use of

bisphosphonates. (See “Drug Therapies – Bisphosphonates,” page 15.)

• Family members should carry documentation of the OI diagnosis to avoid accusations of

child abuse at emergency rooms.

• It is also important to address difficulties with social integration, participation in leisure

activities, and maintaining stamina.

• The treatment plan should maximize mobility and function, increase peak bone mass and

muscle strength, and employ as much exercise and physical activity as possible.

Microscopic studies of OI bone, led by Francis Glorieux, M.D., Ph.D., at the Shriners Hospital

for Children in Montreal, have identified a subset of people who are clinically within the OI

Type IV group but have distinctive patterns to their bone. Review of the clinical histories of

these people uncovered other common features. As a result of this research, two types – Type V

and Type VI – were added to the Sillence Classification. Regarding these types, it is important to

note the following:

• They do not involve deficits of type 1 collagen.

• Treatment issues are similar to OI Type IV.

• Diagnosis requires specific radiographic and bone studies.

Guide to Osteogenesis Imperfecta for Pediatricians and Family Practice Physicians 9

Type V:

- OI Type V is moderate in severity. It is similar to OI Type IV in terms of frequency of

fractures and the degree of skeletal deformity.

• The most conspicuous feature of this type is large, hypertrophic calluses in the largest

bones at fracture or surgical procedure sites.

• Hypertrophic calluses can also arise spontaneously.

• Calcification of the interosseous membrane between the radius and ulna restricts forearm

rotation and may cause dislocation of the radial head.

• Women with OI Type V anticipating pregnancy should be screened for hypertrophic

callus in the iliac bone.

• OI Type V is dominantly inherited and represents 5 percent of moderate-to-severe

OI cases.

Type VI:

- OI Type VI is extremely rare. It is moderate in severity and similar in appearance and

symptoms to OI Type IV.

• This type is distinguished by a characteristic mineralization defect seen in biopsied bone.

• The mode of inheritance is probably recessive, but it has not yet been identified.

Recessively Inherited Types of OI (Types VII and VIII):

• Two recessive types of OI, Types VII and VIII, were recently identified. Unlike the

dominantly inherited types, the recessive types of OI do not involve mutations in the type 1

collagen genes.

• These recessive types of OI result from mutations in two genes that affect collagen

posttranslational modification:

― the cartilage-associated protein gene (CRTAP)

― the prolyl 3-hydroxylase 1 gene (LEPRE1).

• Recessively inherited OI has been discovered in people with lethal, severe, and moderate OI.

There is no evidence of a recessive form of mild OI. Recessive inheritance probably accounts

for fewer than 10 percent of OI cases.

• Parents of a child who has a recessive type of OI have a 25 percent chance per pregnancy of

having another child with OI. Unaffected siblings of a person with a recessive type have a 2

in 3 chance of being a carrier of the recessive gene.

Type VII:

- Some cases of OI Type VII resemble OI Type IV in many aspects of appearance and

symptoms.

• Other cases resemble OI Type II, except that infants have white sclerae, small heads and

round faces.

• Short humeri and femora are common.

• Short stature is common.

• Coxa vara is common.

• OI Type VII results from recessive inheritance of a mutation in the CRTAP gene. Partial

(10 percent) expression of CRTAP leads to moderate bone dysplasia. Total absence of the

cartilage-associated protein has been lethal in all identified cases.

Guide to Osteogenesis Imperfecta for Pediatricians and Family Practice Physicians 10

Type VIII:

- Cases of OI Type VIII are similar to OI Types II or III in appearance and symptoms

except for white sclerae.

• OI Type VIII is characterized by severe growth deficiency and extreme undermineralization

of the skeleton.

• It is caused by absence or severe deficiency of prolyl 3-hydroxylase activity due to

mutations in the LEPRE1 gene.

Additional Forms of OI

The following conditions are rare, but they feature fragile bones plus other significant symptoms.

More detailed information on them can be found in Pediatric Bone: Biology and Diseases,

Glorieux et al, 2003.

• Osteoporosis-Pseudoglioma Syndrome: This syndrome is a severe form of OI that also

causes blindness. It results from mutations in the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related

protein 5 (LRP5) gene.

• Cole-Carpenter Syndrome: This syndrome is described as OI with craniosynostosis and

ocular proptosis.

• Bruck Syndrome: This syndrome is described as OI with congenital joint contractures.

It results from mutations in the procollagen-lysine, 2-oxoglutarate 5-dioxygenase 2

(PLOD2) gene encoding a bone-specific lysyl-hydroxylase. This affects collagen

crosslinking.

• OI/Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome: This recently identified syndrome features fragile bones

and extreme ligament laxity. Young children affected by this syndrome may experience

rapidly worsening spine curves.